William Hoskins

In 2005, an Australian historian contacted me with information about my paternal forebears, specifically my great grandfather who, it was revealed, was the celebrated British Shakespearean actor, William Hoskins. Until this time, I knew little about my father's family except that my grandfather was "some kind of actor" - my mother's dismissive description of her father-in-law. While my father might simply have considered his family history irrelevant, my mother, for reasons only she knew, was at pains to conceal anything concerning my father's family. Consequently, I knew nothing at all of my great grandfather until this recent date.

William Hoskins was a leading actor with the Samuel Phelps company at Sadler's Wells Theatre in London in the mid nineteenth century, and tutor to a young Sir Henry Irving, securing Irving's first acting job for him. It was the era of the actor-manager, and in 1856, Hoskins received an offer he couldn't refuse and emigrated to Australia to take up management of a theatre. The teenage Irving intended to accompany him, but family duties detained him in England where he went on to become the greatest exponent of Shakespeare of 19th Century British theatre, and the first actor knight. Irving never forgot Hoskins and paid him warm tribute in his autobiography.

At various times, Hoskins managed several theatres in Sydney and Melbourne and in New Zealand, and he toured America. His highly acclaimed performances became legend in their time. He died in New Zealand in 1886 and his obituary stated "as a student and critical reader of Shakespeare, he had certainly no superiors in any part of the world".

My grandfather was born Thomas George Parry in New Zealand and was reportedly adopted at birth by Hoskins. Historians deduce that "Parry" was the illegitimate son of Hoskins and an actress in his company and that the adoption was a ploy to avoid scandal. Hoskins trained his son as an actor and Thomas George Parry became George Hoskins, but wanting to escape from his father's considerable shadow, he changed his name for the stage to Paul Creyton (the pseudonym of contemporary American novelist John Trowbridge). As tribute to his father, he gave my father the middle name of Hoskin. But if Douglas Hoskin Creyton was ever cognizant of the relevance of his second name, he gave no indication of it during his short life.

Paul Creyton's was not a starry career, but his notices in the New Zealand press of the late 1800s are extremely complimentary. He left New Zealand for Australia in 1897 and performed in Sydney and Melbourne before establishing his own theatre company in Queensland where he met and married my grandmother who was 20 years younger than he. It's little wonder he opted to settle in Brisbane, where his reviews for such plays as The Snowball, East Lynne and Boucicault's The Shaughraun were glowing. After establishing his own repertory company in Queensland, he abandoned the theatre early in the 20th century and devoted much of his later life to politics, particularly the labor movement in which he became a prominent figure and a staunch activist.

I was thirteen years old when he died at the ripe age of ninety-nine. I remember him as witty and grand, with a booming voice, and my grandmother as a perpetually jolly woman whose voice was warm and rippled with a kind of inner happiness. Her interest in the theatre never waned until her death at ninety-six. When we were children, my mother's irrational dislike of my father's family restricted our visits with them, so my brother's and my recollections of our grandparents, though fond, are fractured. Yet memories of their house by the sea are etched into my brain.

In my grandparents' living room, there were books - a rarity in my parents' home. There was a tall, stately, wind-up gramophone with a goodly collection of discs which I never tired of playing. There was opera - some Verdi, some Puccini, but "don't play the Wagner" my grandmother would plead gently. "Too noisy." And she'd slip The Ride of the Valkyries back onto the shelf and pull out musical comedies of the 1920s, hits from the movies of the 1930s and countless operetta recordings.

One memory of my grandfather remains vivid: when I was ten and he a hale 96, he took me walking around the seaside town to which he'd retired and led me into an empty theatre. I remember his tour of the auditorium, the wings, the dressing rooms. He allowed me to stand alone on the bare stage where I gazed out into the deserted auditorium. After fifty-six years in the profession, I still experience the same thrill of expectation upon entering an empty theatre as I did on that afternoon in 1950.

After his death, on the rare visits with my grandmother, she introduced me to George Bernard Shaw by reading with me from my grandfather's play script of Pygmalion - At fourteen, I played Henry Higgins to her Eliza. We also read from lesser comedies and melodramas she and my grandfather had appeared in such as The Snowball and East Lynne. In the latter, my grandfather played the villain, Sir Francis Levison to my grandmother's tortured heroine, Lady Isabel. It was in the role of Levison in a musical version of the play that my name became prominent in Sydney theatre in the early 1960s. Of this alone, my grandmother was inordinately proud and wrote that she wished my grandfather had lived to see me play the part.

My grandparents' lifelong love of theatre was not inherited by my father and certainly had no place in my mother's view of the universe. The collision between their attitude, and my growing passion for the stage was inevitable. After appearing in minor parts in a handful of plays for the local theatre companies, at the age of eighteen, I auditioned for the inaugural year of Australia's National Institute of Dramatic Art. A handful of my actor friends were accepted by the Institute and duly traveled to Sydney to begin training. I had no response to my audition and presumed I'd failed. A year later, my mother revealed I'd been offered a scholarship but she determined I should not be an actor, so kept the Institute letters to herself and replied to them declining their offer. This was a turning point in my teen life. I left home and took an apartment in the city determined to pursue a career in the theatre by any means available to me. By age twenty, I was well known in my hometown as an actor and as host of my own radio program dedicated to theatre news and interviews. I relocated to Melbourne where I played leads in many radio dramas and within a year, toured Australia in Odets' Winter's Journey (The Country Girl) with the great British star Googie Withers. I celebrated my twenty-first birthday while in this company.

The tour ended in Sydney, the Australian center of theatre, television and radio which, in 1961, was still a considerable force in the entertainment industry. After playing Lorenzo in a spectacular television production of The Merchant of Venice, I began playing leading roles in a string of musical plays at the Music Hall Theatre, two of which I authored. At the age of twenty-four, I was wrenched out of the theatre and into television as one of the three stars of the blockbuster satirical series The Mavis Bramston Show. This groundbreaking show accorded me abiding national notoriety - notoriety as a "personality" which I would escape at age twenty-eight to become a working actor again in London during the 70s.

During these television years in the '60s, on a rare and brief visit to my hometown, I spent a day with my grandmother in her retirement home. It was the last time I saw her. We spent a wonderful day of laughter and a few tears, and I delighted in her immense pride in showing me off to the 'oldies', her co-residents at the home. We spoke briefly of my grandfather, but there was no mention of my great grandfather then, or ever, that I can recall.

Classic movies, indeed the entire history of the cinema, are easily accessible these days. By comparison, theatre and its inhabitants are disposable. Great performances of the recent past reside in our memory, certainly, but beyond the limits of personal recall, many of the theatre's great figures and their performances are forgotten. This sad reality of the nature of theatre notwithstanding, I'm indebted to the historian who gave me details of a long forgotten theatre great from whom, I'm happy to discover, I am descended.

William Hoskins was a leading actor with the Samuel Phelps company at Sadler's Wells Theatre in London in the mid nineteenth century, and tutor to a young Sir Henry Irving, securing Irving's first acting job for him. It was the era of the actor-manager, and in 1856, Hoskins received an offer he couldn't refuse and emigrated to Australia to take up management of a theatre. The teenage Irving intended to accompany him, but family duties detained him in England where he went on to become the greatest exponent of Shakespeare of 19th Century British theatre, and the first actor knight. Irving never forgot Hoskins and paid him warm tribute in his autobiography.

At various times, Hoskins managed several theatres in Sydney and Melbourne and in New Zealand, and he toured America. His highly acclaimed performances became legend in their time. He died in New Zealand in 1886 and his obituary stated "as a student and critical reader of Shakespeare, he had certainly no superiors in any part of the world".

My grandfather was born Thomas George Parry in New Zealand and was reportedly adopted at birth by Hoskins. Historians deduce that "Parry" was the illegitimate son of Hoskins and an actress in his company and that the adoption was a ploy to avoid scandal. Hoskins trained his son as an actor and Thomas George Parry became George Hoskins, but wanting to escape from his father's considerable shadow, he changed his name for the stage to Paul Creyton (the pseudonym of contemporary American novelist John Trowbridge). As tribute to his father, he gave my father the middle name of Hoskin. But if Douglas Hoskin Creyton was ever cognizant of the relevance of his second name, he gave no indication of it during his short life.

Paul Creyton's was not a starry career, but his notices in the New Zealand press of the late 1800s are extremely complimentary. He left New Zealand for Australia in 1897 and performed in Sydney and Melbourne before establishing his own theatre company in Queensland where he met and married my grandmother who was 20 years younger than he. It's little wonder he opted to settle in Brisbane, where his reviews for such plays as The Snowball, East Lynne and Boucicault's The Shaughraun were glowing. After establishing his own repertory company in Queensland, he abandoned the theatre early in the 20th century and devoted much of his later life to politics, particularly the labor movement in which he became a prominent figure and a staunch activist.

I was thirteen years old when he died at the ripe age of ninety-nine. I remember him as witty and grand, with a booming voice, and my grandmother as a perpetually jolly woman whose voice was warm and rippled with a kind of inner happiness. Her interest in the theatre never waned until her death at ninety-six. When we were children, my mother's irrational dislike of my father's family restricted our visits with them, so my brother's and my recollections of our grandparents, though fond, are fractured. Yet memories of their house by the sea are etched into my brain.

In my grandparents' living room, there were books - a rarity in my parents' home. There was a tall, stately, wind-up gramophone with a goodly collection of discs which I never tired of playing. There was opera - some Verdi, some Puccini, but "don't play the Wagner" my grandmother would plead gently. "Too noisy." And she'd slip The Ride of the Valkyries back onto the shelf and pull out musical comedies of the 1920s, hits from the movies of the 1930s and countless operetta recordings.

One memory of my grandfather remains vivid: when I was ten and he a hale 96, he took me walking around the seaside town to which he'd retired and led me into an empty theatre. I remember his tour of the auditorium, the wings, the dressing rooms. He allowed me to stand alone on the bare stage where I gazed out into the deserted auditorium. After fifty-six years in the profession, I still experience the same thrill of expectation upon entering an empty theatre as I did on that afternoon in 1950.

After his death, on the rare visits with my grandmother, she introduced me to George Bernard Shaw by reading with me from my grandfather's play script of Pygmalion - At fourteen, I played Henry Higgins to her Eliza. We also read from lesser comedies and melodramas she and my grandfather had appeared in such as The Snowball and East Lynne. In the latter, my grandfather played the villain, Sir Francis Levison to my grandmother's tortured heroine, Lady Isabel. It was in the role of Levison in a musical version of the play that my name became prominent in Sydney theatre in the early 1960s. Of this alone, my grandmother was inordinately proud and wrote that she wished my grandfather had lived to see me play the part.

My grandparents' lifelong love of theatre was not inherited by my father and certainly had no place in my mother's view of the universe. The collision between their attitude, and my growing passion for the stage was inevitable. After appearing in minor parts in a handful of plays for the local theatre companies, at the age of eighteen, I auditioned for the inaugural year of Australia's National Institute of Dramatic Art. A handful of my actor friends were accepted by the Institute and duly traveled to Sydney to begin training. I had no response to my audition and presumed I'd failed. A year later, my mother revealed I'd been offered a scholarship but she determined I should not be an actor, so kept the Institute letters to herself and replied to them declining their offer. This was a turning point in my teen life. I left home and took an apartment in the city determined to pursue a career in the theatre by any means available to me. By age twenty, I was well known in my hometown as an actor and as host of my own radio program dedicated to theatre news and interviews. I relocated to Melbourne where I played leads in many radio dramas and within a year, toured Australia in Odets' Winter's Journey (The Country Girl) with the great British star Googie Withers. I celebrated my twenty-first birthday while in this company.

The tour ended in Sydney, the Australian center of theatre, television and radio which, in 1961, was still a considerable force in the entertainment industry. After playing Lorenzo in a spectacular television production of The Merchant of Venice, I began playing leading roles in a string of musical plays at the Music Hall Theatre, two of which I authored. At the age of twenty-four, I was wrenched out of the theatre and into television as one of the three stars of the blockbuster satirical series The Mavis Bramston Show. This groundbreaking show accorded me abiding national notoriety - notoriety as a "personality" which I would escape at age twenty-eight to become a working actor again in London during the 70s.

During these television years in the '60s, on a rare and brief visit to my hometown, I spent a day with my grandmother in her retirement home. It was the last time I saw her. We spent a wonderful day of laughter and a few tears, and I delighted in her immense pride in showing me off to the 'oldies', her co-residents at the home. We spoke briefly of my grandfather, but there was no mention of my great grandfather then, or ever, that I can recall.

Classic movies, indeed the entire history of the cinema, are easily accessible these days. By comparison, theatre and its inhabitants are disposable. Great performances of the recent past reside in our memory, certainly, but beyond the limits of personal recall, many of the theatre's great figures and their performances are forgotten. This sad reality of the nature of theatre notwithstanding, I'm indebted to the historian who gave me details of a long forgotten theatre great from whom, I'm happy to discover, I am descended.

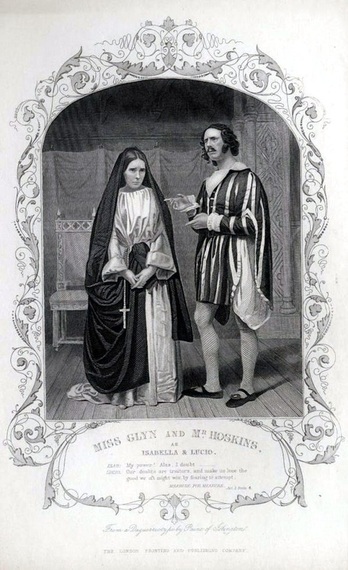

William Hoskins as Lucio in Shakespeare's

Measure For Measure ca. 1850

Measure For Measure ca. 1850

The Mavis Bramston Show

1964

Carol Raye, Gordon Chater, Barry Creyton, June Salter

1964

Carol Raye, Gordon Chater, Barry Creyton, June Salter